The Guyana government’s largest proposed renewable energy project has been delayed, leaving a gap that may be filled by natural gas. The implications of this for Guyana’s transition plan are significant, but the government has always held that it has the right to use its resources for the benefit of its people.

Five years ago, ExxonMobil discovered significant oil and gas reserves offshore. Since then, the company has been increasing oil production every year, now producing more than 600,000 barrels of oil per day. This rapid growth is set to make Guyana the world’s largest oil producer per capita and has resulted in the country becoming the world’s fastest-growing economy.

With this rapid economic growth, Guyana faces new challenges, particularly in meeting its increasing energy needs. The government has outlined a plan to increase electricity generation while also reducing emissions associated with power generation, in line with global concerns about climate change.

One of the key projects proposed is the Amaila Falls Hydropower Project (AFHP). Conceived in the 1970s, the AFHP aims to harness renewable energy from the Amaila Falls, a remote waterfall in the southwestern Region 8. The project was intended to significantly expand Guyana’s electricity generation capacity and reduce its dependence on imported fossil fuels like heavy fuel oil and diesel.

In 2009, under the Low Carbon Development Strategy—a plan for the country’s sustainable development—the Guyanese government secured funding through a partnership with Norway focused on rainforest conservation and green energy initiatives. By 2012, the project had advanced considerably, with private investor Sithe Global involved and financial arrangements being solidified, managed by the Inter-American Development Bank. The hydropower plant was expected to deliver 165 megawatts (MW) of power, promising substantial reductions in energy costs for consumers.

However, in 2013, Sithe Global withdrew from the project due to political opposition within the Guyanese parliament. Opposition parties combined their strength to hold a majority and inhibited the progress of the project. The government that was championing the project lost the election in 2015, and the new administration did not pursue the project.

In 2020, the previous government regained power and decided to revive the AFHP. China Railway Group Limited was granted a no-objection to develop the project, targeting completion by 2027. However, after six months of negotiations, an agreement on a suitable financial model could not be reached, and the contractor pulled out. Consequently, the Guyanese government issued a new request for proposals in December 2023 under a build-own-operate-transfer (BOOT) model. Four bidders emerged:

– Lindsayca CH4 Guyana Inc.

– Rialma

– China International Water and Electric Corporation

– A joint venture comprising OEC, GE Vernova, and Worley

The government stressed the importance of adherence to timeframes, economic viability, and the expertise of potential partners to secure the contract.

As of September 2024, the government has not made progress in selecting a successful bidder to move the project forward. The 165 MW AFHP, which is the first large-scale renewable energy project for Guyana’s energy transition, has been delayed. Guyana’s Vice President, Bharrat Jagdeo, stated during a September press conference that the government might have to either engage the best among the bidders or seek fresh bids. He stressed that the AFHP remains crucial for achieving Guyana’s desired energy mix.

Implementing the AFHP necessitated thorough environmental and technical assessments. An environmental impact assessment was conducted years ago, to evaluate potential effects on the pristine rainforest, biodiversity, and indigenous communities in Region 8, where the waterfall is located. Key concerns included deforestation, disruption of wildlife habitats, and social implications for local populations. However, the impact is expected to be minimal. To mitigate risks, strategies such as preserving protected zones around sensitive areas were proposed.

From a technical standpoint, the project’s remote location presents challenges. Major costs are associated with constructing access roads to the site and building a 270-kilometer transmission line to deliver electricity to population centers on the coast. Managing water flow to ensure reliable energy generation during dry seasons is also a critical consideration. These factors, combined with inflationary pressures, pushed the projected cost to US$840 million by 2020, with the potential for further increases due to rising expenses.

With the current state of affairs, the project would no longer be funded through the Guyana-Norway Partnership, which was based on funds received for forest conservation. The government expects the successful bidder to secure financing independently, operate the project, and eventually transfer it to the government.

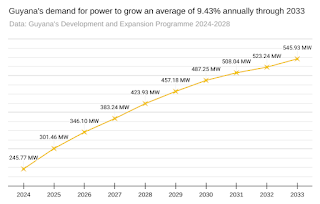

It is important to understand Guyana’s current generation capacity and demand forecast. The Guyana Power & Light Inc. (GPL), the state electricity provider, published the Development and Expansion Program 2024-2028, which notes a significant increase in projected electricity demand, driven by unprecedented growth in the number of customers and energy intensity per customer.

These projections consider all the infrastructural developments that are currently underway and those expected in the future. The driving factors include:

– Infrastructure projects like roads and bridges

– Government housing projects providing subsidized plots and assisting with building homes

– Expansion of education through building schools

– Improvement of healthcare by building hospitals

– Private sector investments in hotels and apartment complexes

– Commercial and industrial projects to service the oil and gas sector and other rapidly expanding sectors

In GPL’s expansion program compiled in 2023, it is stated that peak demand in 2024 is expected to be 245.77 MW. As of September 2024, Prime Minister Mark Phillips said that Guyana’s peak demand is 205 MW. However, an increase is expected during the Christmas season. The expansion document also stated that GPL’s total firm generation capacity stood at 186.3 MW at the time of its compilation. Due to generation shortfalls, there were frequent power outages. To address the shortage, the government chartered a 36 MW power ship for two years, starting in the second quarter of 2024. However, demand continues to increase, and in September 2024, power outages persist. To ensure sufficient power supply, especially during the Christmas season, the government has invited proposals for an additional 60 MW of net power generation (also fossil fuel) as a temporary measure.

In Guyana’s energy generation expansion plan, there are more projects besides the AFHP:

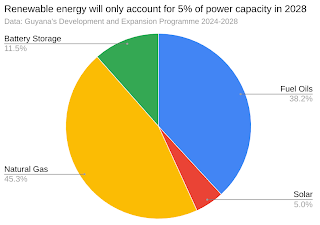

– Solar Projects: The government expects that by 2028, solar projects will generate 32.7 MW of non-firm capacity, the only renewable source in the energy mix for the period.

– Gas-to-Energy Project (Phase One): Expected to start production in 2025, this project is pursued in partnership between the government of Guyana and ExxonMobil. It will use offshore natural gas transported through a pipeline at a rate of 50 million cubic feet per day. A major aspect of this project is the construction of a 300 MW power plant, contributing to the 295 MW of natural gas power projected by GPL in its 2024-2028 expansion plan.

In GPL’s report, the AFHP is still considered a vital part of Guyana’s long-term expansion plan, but its start date—once intended to be 2027— has been pushed back to 2029. This has, without a doubt, been impacted by the trouble the government has encountered in its pursuit of this project. With demand for power expected to continue to grow, the government needs to continue to add projects so there is enough supply for the growing country.

In September 2024, the government published a notice inviting proposals for Phase Two of the Gas-to-Energy project. Phase Two would include a 250 MW power plant added to Phase One, resulting in 550 MW supplied by gas-fired power.

The introduction of Phase Two of the Gas-to-Energy Project impacts Guyana’s energy mix plan. The government had previously committed to reducing emissions by 70% by 2028 as part of its Low Carbon Development Strategy. The addition of more gas-fired power, while emitting less than heavy fuel oil and light fuel oil, expands Guyana’s dependence on fossil fuels. However, with the delay to the government’s largest renewable energy project, it may not have much of a choice.

The government must deliver gas-fired power in 2025 to meet the country’s development needs, as there is no other viable alternative that can be delivered by that time. Furthermore, Phase Two of the Gas-to-Energy project appears to be a big part of the plan to make up for Amaila’s delay.

Guyana faces the challenge of balancing its immediate energy needs with its long-term climate goals. The government faces criticism urging it to be more aggressive in pursuing renewable energy projects. Guyana’s Vice President, Bharrat Jagdeo, has often responded to such criticisms by emphasizing that Guyana has the right to use its resources, including its recently discovered petroleum resources, for the development of its people. He argues that it is unjust to suggest that Guyana should not extract these resources for its benefit, especially since the country has not historically been a significant contributor to the climate crisis. It has excellent environmental credentials, conserving more than 80% of its landmass as forests.

While natural gas is still a fossil fuel, using it as a replacement for fuel oils is expected to result in a reduction of emissions associated with electricity generation. Vice President Jagdeo said that once Phase One of the Gas-to-Energy project begins generation in 2025, the government will place its fuel oil plants in reserve.

This story was published with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture of Climate Tracker and Open Society Foundations.