By Kemol King

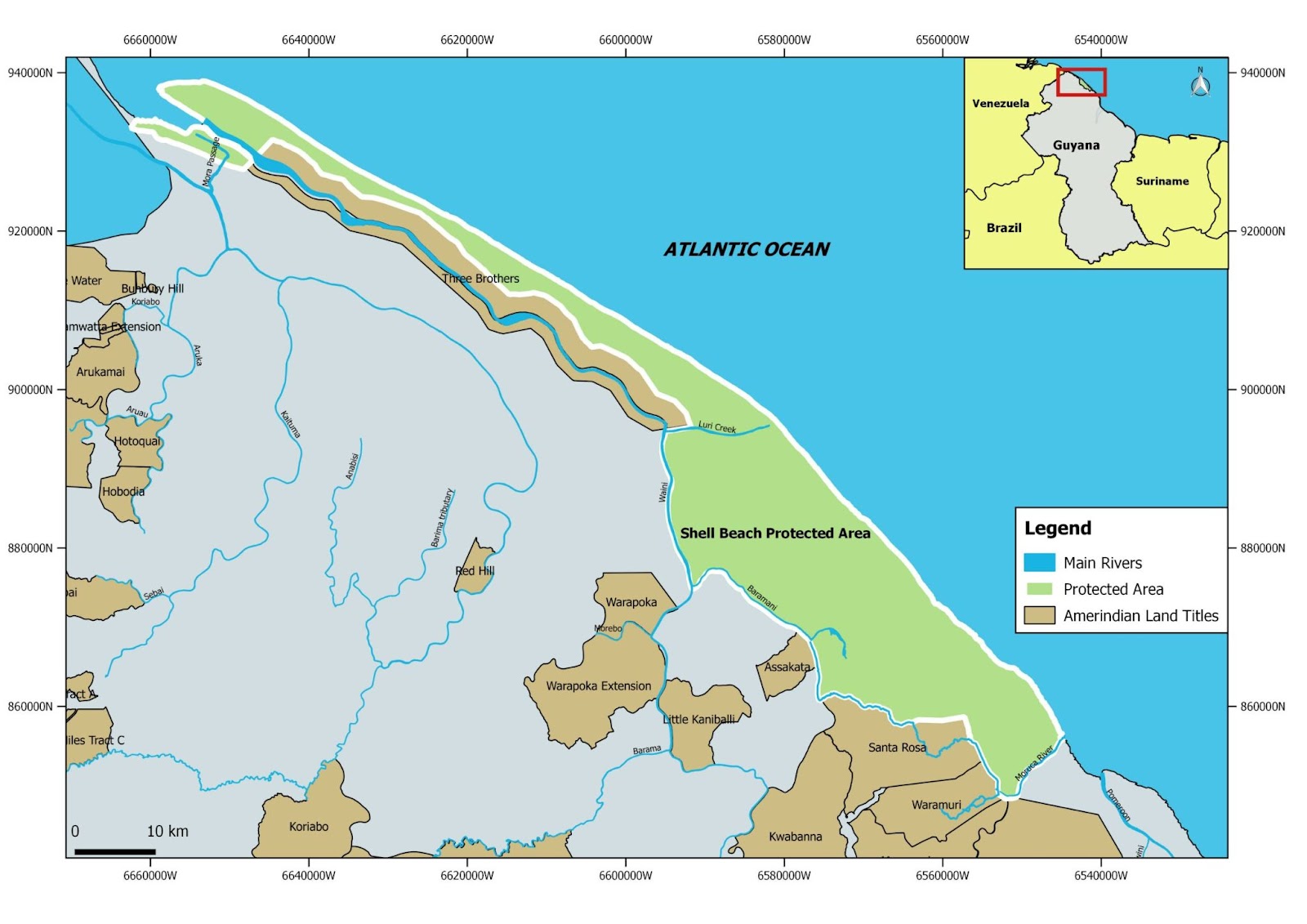

Guyana’s Shell Beach Protected Area is home to rich biodiversity, including four species of endangered sea turtles: Green, Hawksbill, Leatherback, and Olive Ridley. These species depend on the coastline for nesting, but climate change is putting their future at risk. One of the biggest threats facing these turtles is beach erosion, a consequence of rising sea levels caused by global emissions, among other things.

Worsening the situation, the PAC found that erosion has caused waterlogging in natural nests, spoiling the eggs before they hatch. The fragile balance of nature at Shell Beach is becoming more precarious each year, putting these turtles—already on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List—at even greater risk.

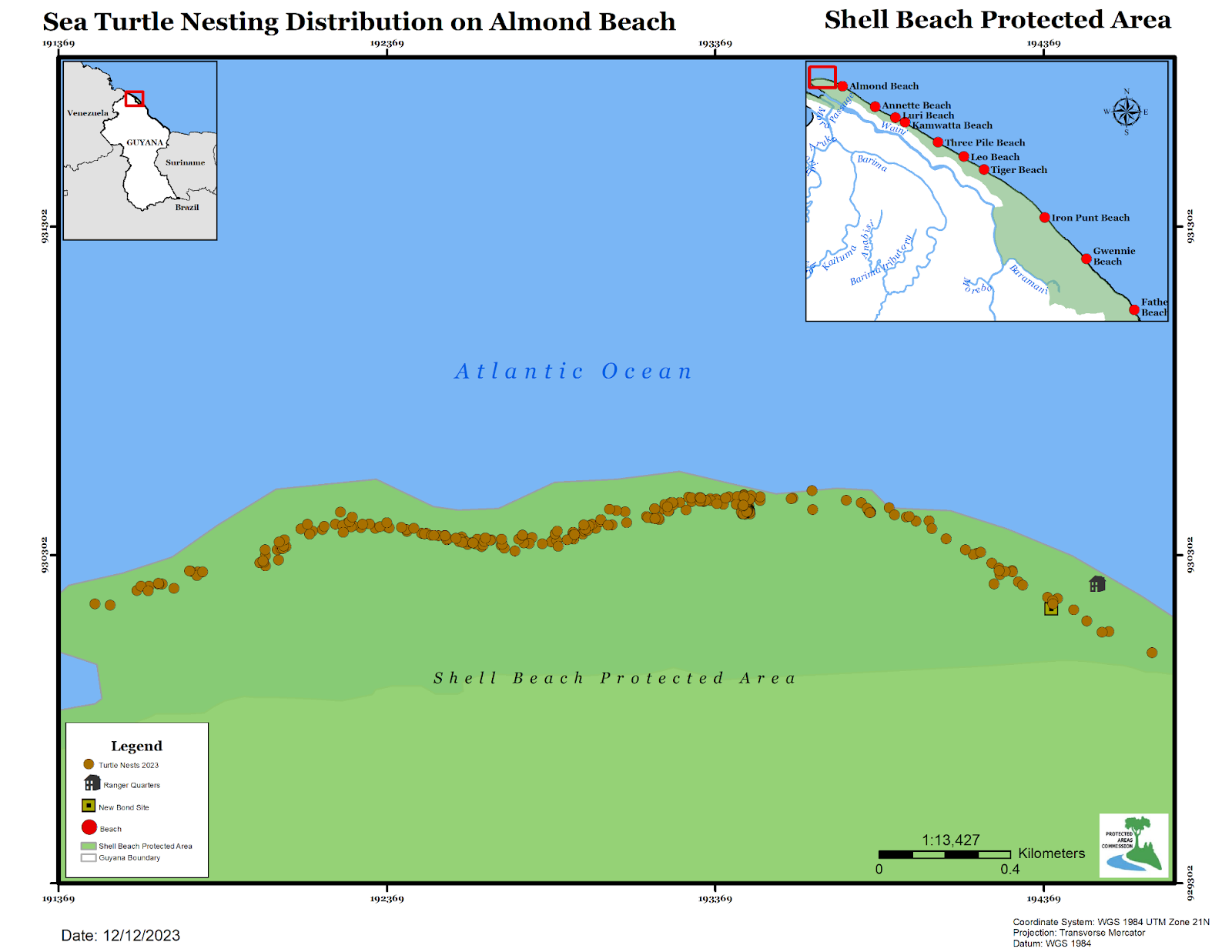

Efforts are being made by the PAC to monitor the turtles, with rangers stationed at the beach during the nesting seasons. “Turtles nest at different beaches found within the [Shell Beach Protected Area], however, the PAC only monitors two of the ten beaches, which are Almond Beach (the main nesting beach) and Tiger Beach, which is our secondary beach and is monitored at two-week intervals,” the Commission stated.

Saltwater intrusion is also affecting farmland and freshwater sources, impacting fishing and agriculture, the PAC said.

Entire families have been displaced, and some have migrated to nearby Moruca. The Almond Beach school was closed due to advancing erosion, leaving a once-thriving community in decline. “Currently, there is only one household, comprising four persons residing at Almond Beach, and 15 persons living on Father’s Beach,” the PAC stated.

Of the 10 beaches along the Shell Beach coastline, the Almond and Father’s Beaches are the two with human settlements, located at the northernmost and southernmost ends respectively. The last family at Almond Beach is preparing to leave, aided by funds from the sale of Guyana’s carbon credits, which the government allocated to indigenous communities. The Toshao (elected leader) of Almond Beach, Arnold Benjamin, said they are using the funds to build housing for the family in nearby Mabaruma. Once construction is complete, the family will relocate, leaving the PAC rangers as the only remaining human settlement.

For these indigenous people, among Guyana’s first climate refugees, the displacement is a stark reminder that the effects of climate change are not distributed equally. They are being forced to adapt to a crisis they did not create, while industrialized nations continue to drive emissions—a poignant example of climate injustice. This state of affairs echoes across the globe, where marginalized communities and species face the consequences of climate change.

Developed countries have a big role to play in climate justice due to their emissions record and their capacity to respond to climate change. They are expected to provide financial support to developing nations, lead in emission reduction efforts, and assist with adaptation strategies. This allows for vulnerable countries to receive the support needed for a fair and equitable global response to climate change.

This story was published with the support of the Caribbean Climate Justice Journalism Fellowship, which is a joint venture of Climate Tracker and Open Society Foundations.